Egypt is a broken country. Netflix’s Cleopatra provocation is the last thing it needs

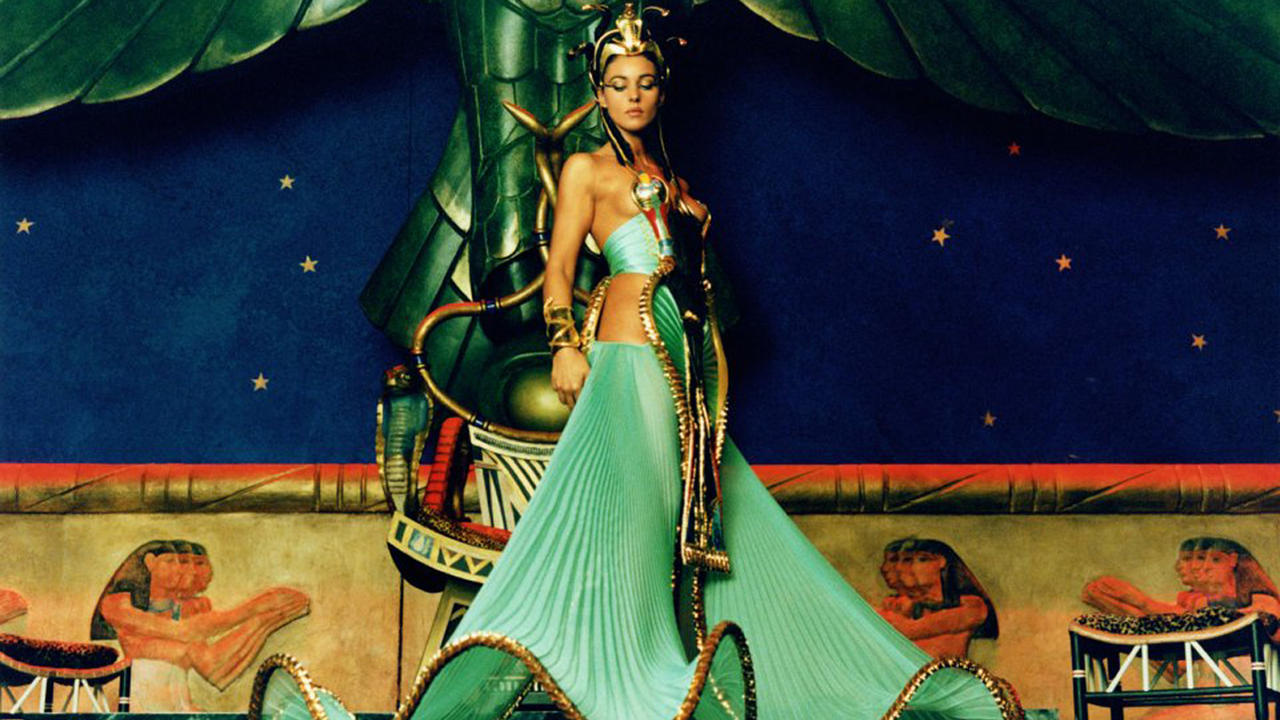

“Is she Black?” A Roman noblewoman asks her friend about Cleopatra in Cecil B DeMille’s garish Hollywood epic starring Oscar winner Claudette Colbert as the titular Egyptian monarch.

An exotic enigma treated with a mix of fascination and revulsion by the Roman elite, the race of Ancient Egypt’s most famous queen is not what seems to preoccupy the Roman court - it’s her looks.

“Do you think she’s beautiful?” Another aristocrat wonders in another scene, before a distinctly Caucasian and scantily clad Colbert appears.

Race was not the hallmark of Hollywood at the time. Black talent was shut out of an industry largely run by white executives who deemed African-American actors and directors unmarketable and unworthy of being placed at centre stage.

Contrary to popular belief, Black stories were always part of American cinema, existing in the margins and suppressed by a Hollywood machine whose marketing powers were too strong for these independently made films to combat.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Hollywood’s embrace of Sidney Poitier in the 1950s and 60s and the subsequent Blaxploitation cinema of the 70s was not driven by an evolving woke attitude among the same white executives: Hollywood simply realised there was a market for black stories – a market too profitable to ignore.

Money-making, and not genuine progressivism, has always been the driving force in Hollywood. Netflix’s Queen Cleopatra is no different.

No other film or TV series has generated the colossal buzz that met Netflix’s latest creation this year. The casting of a Black performer as Cleopatra was always going to incite controversy, especially among Egyptians growing increasingly hostile towards Afrocentrism.

The ‘race card’

Cleopatra is the second season of a docufiction series produced by Jada Pinkett Smith about historical African queens – a celebration of Black female culture long suppressed by Europe and the West.

The first edition, streamed in February 2023 during the US Black History Month, did not set the charts alight.

Titled Njinga, it chronicles the life of the 17th-century ruler of Ndongo and Matamba in southwest Africa (modern Angola). The show interweaved academic interviews with corny dramatisation, giving the endeavour the feel of disposable daytime TV: sluggish, boring in form, and too simplistic to spur any intellectual debate.

Njinga did not crack Netflix’s top 10 charts and was not trending at any point in the Middle East. Given the modest ratings, the hysteria surrounding Cleopatra felt quite suspicious.

The low artistic ceiling of the first series did not encourage faith for the new season; the historical accounts were too safe and too predictable to instigate hope for provocative scholarly discourse.

Director Tina Gharavi’s track record did not reveal a visionary filmmaker challenging the staid status of Anglophone documentary filmmaking.

As sincere as her previous work may be – the most famous of which is I Am Nasrine about the plight of Iranian refugees in the UK – it is, nonetheless, contrived, hackneyed and forgettable in its storytelling; the kind of non-fiction made to fill airwaves with content.

Netflix and Pinkett-Smith had only the race card, and judging by the endless press Cleopatra has received and the elevated position season two scored in the charts, the pair have pulled off a coup of marketing brilliance.

‘Predictable point of view’

Now that Cleopatra is streaming, was the series worth the hype? The answer is a big no. Yet the most shocking aspect of the wretched affair is that the series does not tackle Cleopatra’s race to begin with.

In fact, African Queens offers nothing new about the Egyptian icon: this is the same old story told in predictable fashion from the same predictable point of view.

The four episodes present the awfully familiar linear narrative of Cleopatra’s rise and fall: from her ascendance to Egypt’s throne in 51 BCE, through to her famed affair with Julius Caesar, to her marriage to Mark Antony and the couple’s suicide following a Roman invasion in 30 BCE.

Cleopatra adopts the same format that made Njinga a slug of a watch: medium close-up interviews with academics – all hailing from American and British institutions – punctuated with dramatised episodes from Cleopatra’s life. All characterised by hammy acting, modest production values and insipid direction.

Gharavi leaves the monotonous narrative structure unchallenged and the result is an exceptionally bland watch that feels like filmmaking on autopilot.

With no distinctive aesthetic point of view on offer and nothing intellectually novel to engage with, Cleopatra swiftly becomes a test of patience before it even reaches episode two.

Its destitute 11 percent fresh rating on Rotten Tomatoes shows that even the more lenient international press found no virtues in the show.

The producers know they’re running on empty, so it’s no surprise the Egyptian monarch’s race is introduced early on, albeit in a rushed, unscientific fashion.

The race card was nothing more than a cheap marketing ploy, a sensationalistic move by a network whose raison d'etre is attracting subscribers and nothing else

In its first moments, Smith promises a revelation of Cleopatra’s “Truth,” setting the stage for the epic revelation the viewers have been anticipating.

Moments later, academic Shelley P Haley of Hamilton College says: “My grandma told me, ‘I don’t care what they tell you in school. Cleopatra was Black.’”

Dr Islam Issa, a British-Egyptian literary critic and historian at Birmingham City University, then states that “anybody can imagine Cleopatra the way they like. I imagine her to be curly-haired like me.”

And that’s essentially the entire discourse the series offers on Cleopatra’s race.

Viewers eager for a proper discussion on the subject will be thoroughly disappointed.

No mention of Cleopatra’s race is uttered again throughout the show. At the very end of the series, Haley says: “I wanted to show Cleopatra for what she was: a great African queen.”

In the face of the countless screaming matches and lawsuits on cultural appropriation and representation, this very generic statement comes off as an enormous anti-climax.

‘Marketing ploy’

Admittedly, Netflix did stress in their statement last month that: “(Cleopatra’s) ethnicity is not the focus of (the series), but we did intentionally decide to depict her of mixed ethnicity to reflect theories about Cleopatra’s possible Egyptian ancestry and the multicultural nature of ancient Egypt.”

Nevertheless, to drum up interest, the show’s trailer gave the impression that the queen’s race is the focus of the series by prominently placing Haley’s aforementioned statement.

The trailer amassed more than three million views on YouTube compared to Njinga’s 240,000.

Irrespective of the Netflix statement, everyone jumped on the "Black Cleopatra" bandwagon: nearly every news outlet dedicated sizable coverage to what was dubbed “blackwashing” along with Egypt’s exaggerated reaction to the series.

No one cared to wait to watch the series; everyone had a set of prejudgments they were ready to unleash.

In the context of the actual show, Netflix is blameless. Beyond Haley’s truncated and unbacked statement, the series does not attempt to persuade viewers that Cleopatra might have been Black.

Roman emperor Octavian’s campaign against Cleopatra is depicted as largely xenophobic and misogynistic – her possible African roots play no role in his antagonism.

Adele James, who does a solid job portraying the Egyptian icon in spite of the insipid dialogue, could certainly pass on for an Egyptian. She is not miscast and her racial background is a non-issue given the depoliticised nature of the series.

The race card was nothing more than a cheap marketing ploy, a sensationalistic move by a network whose raison d'etre is attracting subscribers and nothing else.

A western gaze

Cleopatra’s story has been done to death since the beginning of cinema. More than 20 adaptations in film and TV have been made about the Egyptian queen, including two Bollywood adaptations and an Asterix & Obelix entry featuring Monica Bellucci in the role of Cleopatra.

Netflix promised a Cleopatra “you haven’t seen before” but that is not the case.

The platform teased a show whose emphasis would be on Cleopatra’s intellect but Gharavi does not stray from the same white male gaze she has criticised, fetishising Cleopatra’s gaudy customs, love life and unabashed sexuality.

More problematic, in casting James, she chose a striking beauty with a perfect figure. In doing so, Gharavi and the producers succumb to oppressive western standards of beauty instead of defying them.

Historical accounts accentuate Cleopatra’s brilliance and charisma; her physical beauty has always been an issue of debate.

The former never comes across in the overegged dramatisation that constantly attempts to come up with justifications for the queen’s watered-down darker side.

Cleopatra may have killed her husband-brother and executed her son, but she did so out of sheer will for survival.

James is no less of a beauty than Colbert, Elizabeth Taylor or Bellucci, but her overearnestness and lack of edginess render her less interesting than those previous incarnations.

Netflix steers away from thorny politics but is always upfront about its faux-liberal gender and sexual politics

Netflix steers away from thorny politics but is always upfront about its faux-liberal gender and sexual politics. Queen Cleopatra’s is no different.

The series champions Cleopatra’s strength as a female leader, marvels at her daring promiscuity and polyamory, and hints at her bisexuality.

These are the same politics habitually associated with Netflix shows: sex positivity, as well as gender politics and fluidity.

Most liberal thinkers, including this writer, take no issue in advocating that agenda but the problem with Cleopatra and other Netflix shows is the blatant and oversimplistic fashion in which these issues are presented.

Cleopatra and Egypt today

Queen Cleopatra does not touch on subjects that could resonate with contemporary Egypt.

An analogy between the contemptible treatment of Egypt by Rome, and the IMF and the Gulf’s behaviour towards modern Egypt could at least have been hinted at, but that never happens.

Instead, the show transpires as a hollow allegory, irrelevant to what is happening in Egypt today.

In response to Netflix, an independent documentary feature directed by white South African Curtis Ryan Woodside was published on YouTube on the same day as Queen Cleopatra.

The film is comprised entirely of interviews, including with an Egyptian filmmaker and “researcher” of undetermined credentials on the subject, and the infamous Egyptian archaeologist Zahi Hawass, who sets out to prove that Cleopatra is not Black before embarrassingly claiming his “closest friends are Black”.

Hawass’ arguments are half-baked and unconvincing, especially for anyone with a semblance of knowledge on how history is relayed and propagated.

Woodside’s poorly-made documentary stinks of xenophobia, emphasising the queen’s Macedonian’s background as a number of interviewees echo Smith’s intention of telling “Cleopatra’s truth”.

In both cases, filmmaking and aesthetic value take a backseat to hot-button issues, and there is no zestier issue at the moment than race.

In the infinite coverage of the series, artistry was not questioned once anywhere. Everyone wanted to be a part of the conversation, and artistic value was passed on for being too serious and convoluted an aspect of the series; one not as sexy as the furore of a nation against the seemingly inaccurate racial depiction of its most famous female leader.

The issue of representation

As a member of a minority group, a secular Coptic unnationalistic Arab, screen representation is a major concern of mine; a concern that should routinely be scrutinised and interrogated. But when representation becomes the only area of censure in film and TV, a stand must be taken.

Over the last decade, screen representation has spawned a large industry featuring organisations and writers whose bread and butter is offering very black and white interpretations of how minority groups are and should be portrayed.

Film and art history is never part of the conversation; profound philosophical inquiries about art and morality are usually brushed aside; and, most frustratingly, the political use of aesthetics is constantly neglected.

For the mainstream press, and for many young cultural commentators, it did not matter how the show was treating Cleopatra’s legacy or what type of storytelling tools it uses to dispatch her story. All that mattered is her skin colour and race and what it all signifies.

Lots of ink has been spilled on the Egyptian racial attitude towards blackness, but in the heat of the moment, the nuances of this highly complex matter have been lost in the shuffle.

Egypt’s antagonism towards Afrocentrism has been more calmly discussed after the cancellation of the Kevin Hart performance in February. Various Egyptian researchers ventured to explore Egypt’s problematic relationship with Pharaonic history.

In the best discussion this writer has listened to on the subject, exiled Egyptian writer Belal Fadl and the outstanding London-based Egyptian researcher and novelist Shady Lewis Botros highlight the fact that our new-found kinship to Ancient Egypt was mostly established at the beginning of the 20th century as a means for fighting British colonial rule.

The Egypt of today is a broken country without a saviour. The Netflix provocation is the last thing this nation needed

The objective behind the rise of Egyptology was, ironically, no different than the one that gave birth to Afrocentrism – a movement that similarly desired to reclaim African history away from colonial influence.

A large chunk of the Egyptian reaction towards Netflix’s Queen Cleopatra is unquestionably racist in nature, but it does not exist in isolation: it’s not intrinsically malicious in other words.

Many Egyptians remain colonised by white European standards of beauty; many are wary of the cultural heritage the West has plundered for centuries; many feel helpless and confused against affluent western forces – namely the IMF and its American and European backers – that continue to shape Egypt’s destiny.

Nothing should excuse the racist attacks that Gharavi and James were subjected to, but this is no mere case of a people who feel threatened by an actor's skin colour as the latter put it in a recent podcast.

Egypt is still struggling with a moment of “collective defeat” as Botros put it: the worst economic crisis in a generation; the death of the middle class; the growing vitriol towards the nation’s most unpopular leader who cannot be unseated (and who has been backed by the US and Europe); and the growing influence of a Gulf region adamant on buying the country for cheap.

Not since the Six Day War defeat have Egyptians felt so hopeless and so helpless.

The Egypt of today is a broken country without a saviour. The Netflix provocation is the last thing this nation needed.

For a country that no longer possesses anything, not even the right to self-determination, a mere hint of a reframing of their own history – perhaps the last thing they seemingly own – could not have gone by as casually as pundits ignorantly expected it to.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.

.jpg.webp?itok=beA1s9yB)