The Holy Land and Us: BBC documentary a 'monumental' moment for Palestinians

It is important that Palestinians are the narrators of their own stories, so I was initially apprehensive about the shared aspect to The Holy Land and Us, and its "both sides" format.

But I was supported by so many Palestinians, who encouraged me and offered advice during the preparation period.

I was particularly nervous that the programme would hurt or misrepresent people, and I expected a backlash from Palestinians who feel strongly about media coverage of their plight - because I myself am impassioned about Palestine and its coverage.

This is the first time we have been allowed to share our stories in such a brave way

So it was a relief to see my inbox inundated with poignant messages after the documentary aired, many sharing their own families’ stories of dispossession and being uprooted - and raising the fact that this injustice has been largely unrecognised until now.

Many messages used the words “groundbreaking” or “unprecedented” and expressed a sentiment that I myself felt - that we Palestinians have never been acknowledged in this way before.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

It always felt like we didn’t matter. And while there is pain that it has taken so long for our stories finally to be told, I know many Palestinians are celebrating the broadcast of the programme as a starting point.

Anything about Palestine always evokes a strong reaction. We get it from all angles - and even when there is something to celebrate, it is often held up for intense scrutiny. I noticed a comment in a previous Middle East Eye article, “The Palestinians are set up to fail”.

While I certainly appreciate the "both sides" format can be problematic and particular scenes in the programme make me deeply uncomfortable, to not acknowledge what it does achieve could be short-sighted.

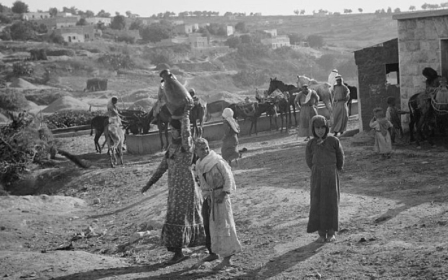

For many of us, our parents or grandparents were so deeply traumatised by Nakba, the catastrophe of 1948, that certain things were unspeakable. It took notable resilience, courage and strength for elderly Nakba survivors to speak about fleeing Deir Yassin or leaving Jaffa in a truck, not to return for another 75 years.

I commend Shereen Malherbe, who learnt that 22 members of her family were killed in the Deir Yassin massacre by Zionist militia and yet, at the end, has inspiring durability to speak of hope and to spare a moment for the Palestinians who remain, and continue to raise families there despite harsh conditions.

I was floored by Zuhadia Radwan, a Deir Yassin survivor who planted a kiss on Shereen’s cheeks for every one of her relatives killed.

I am proud of Joanna Carolan, who spoke of the “injustice” of having her family's orange groves taken away, while her grandfather was fenced inside a ghetto for Palestinians who managed to stay in Jaffa after 1948.

I admire the dignity and decorum shown by Joanna’s uncles Nicholas and Munir, as they stood on the site of what was once their beloved family home - now a car park. “I am happy to be back again, but still… I wonder.”

I, myself, am almost reluctant to use the word "victim", as it is not a term Palestinians like to associate themselves with.

However, when I watch The Holy Land and Us, it feels clear to me who the victims of the 1948 catastrophe were.

I would like to think the audience is intelligent enough to reach their own conclusions after seeing how much the Palestinians lost, or rather, how much was taken from them. As my final comment in the film states, “These lands were not empty. They were emptied.”

Recovering Palestinian history

You cannot deny we were there. For the first time ever, I was given physical evidence of this, thanks to the documentary’s research team.

They discovered a photograph from the 1850s of my ancestor - a Muslim Bedouin sheikh who ensured the protection of both Christian and Jewish communities in the Galilee.

Not to mention seeing with my own eyes official land documents proving we actually owned the land in the village my family fled from.

My own father never even knew such a document existed. We only knew our truth from words passed down from generations. Now we have tangible evidence that cannot be denied or disputed. Finally.

I can say with certainty that every Palestinian will have had some experience of someone intentionally challenging or disputing their very existence.

It was only last week that Israel’s finance minister said, “There's no such thing as Palestinians.” So one might say, the bar is low.

It is dizzying to consider that my great-great-great-grandfather is buried under the earth in Palestine, and yet as I say in the documentary after my experience at Israeli immigration, I cannot even access the country easily.

Of course, an hour and a half of intrusive questioning is nothing compared to what a Palestinian faces at a checkpoint, but the detail of that lies in another show. This show is about 1948. And it is crucial to go back to the root of the problem in order to empathise with what continues to happen today. As 90-year-old Abu Essam expressed, “We are still waiting for our return until this day.”

The start of a conversation

As Palestinians, we are absolutely up against it. Realistically, we all know there was only one way to make this particular BBC programme at this particular moment in time.

If every Palestinian boycotted the opportunity to partake in it, we would render ourselves even more voiceless. But I will not be defeatist.

When I was contemplating with trepidation the role of co-presenting, an industry friend of mine advised, “Don’t think of this as a full stop, as the end point.”

It is the start of the conversation, a wider conversation on British national television, finally recognising the scale of what Palestinians suffered.

It is frustrating it took 75 years for this moment to come, but that does not mean we cannot celebrate this first step, and look ahead to the future platforms for Palestinians the show will create.

In two episodes, The Holy Land and Us cannot tackle everything, nor does it try to. But it succeeds in amplifying the voices of three British Palestinians, all of whose family was displaced in one form or another.

I know from speaking to other Palestinians that it is not purely optimism when I say there has been a distinct shift in the discourse, most notably since May 2021. Before this time, I knew Palestinians who would describe themselves as Jordanian to avoid uncomfortable or hateful comments.

I myself went through a strange period of not bringing up the "P" word in auditions. But as I say at the end of episode two, “We are not Jordanian. We are Palestinian.” There is no time like the present to revive and celebrate our roots, heritage and identity, our tatreez, our dabke, our literature, the long history of civil society and culture - all of which was shattered in 1948.

As Joanna says in episode two, “It is a reminder of the life that was, that was one day taken away.”

I strongly believe people need to watch this show. I hope it will inspire people to see Palestine through a new lens and educate millions of viewers - the non-initiated - who know so little about this catastrophe. Many of my British friends with no connection to the Arab world knew almost nothing about Palestine beyond what I have painstakingly tried to explain.

They expressed, with shock, that they had no idea so many Palestinians were displaced and in such a violent manner. To finally have this validated and fact checked on screen, rather than just having to take our word for it, is monumental.

This is the first time we have been allowed to share our stories in such a brave way, never seen before in the public domain. That means something.

To quote one of the Palestinians who reached out to me, the loss we feel “is a grief that is unregistered. A trauma ignored is a wound that cannot heal and it feels as though this show is starting that process for people who need it.”

The Holy Land and Us : Our Untold Stories aired earlier in March on BBC Two and was directed by David Vincent for Wall to Wall. It explores what happened in Palestine in 1948 and is co-presented by Rob Rinder and Sarah Agha. The programme is available on BBC iPlayer now.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.