Ramadan TV 2023: Arab alpha males, dodgy sheikhs and toothless comedies

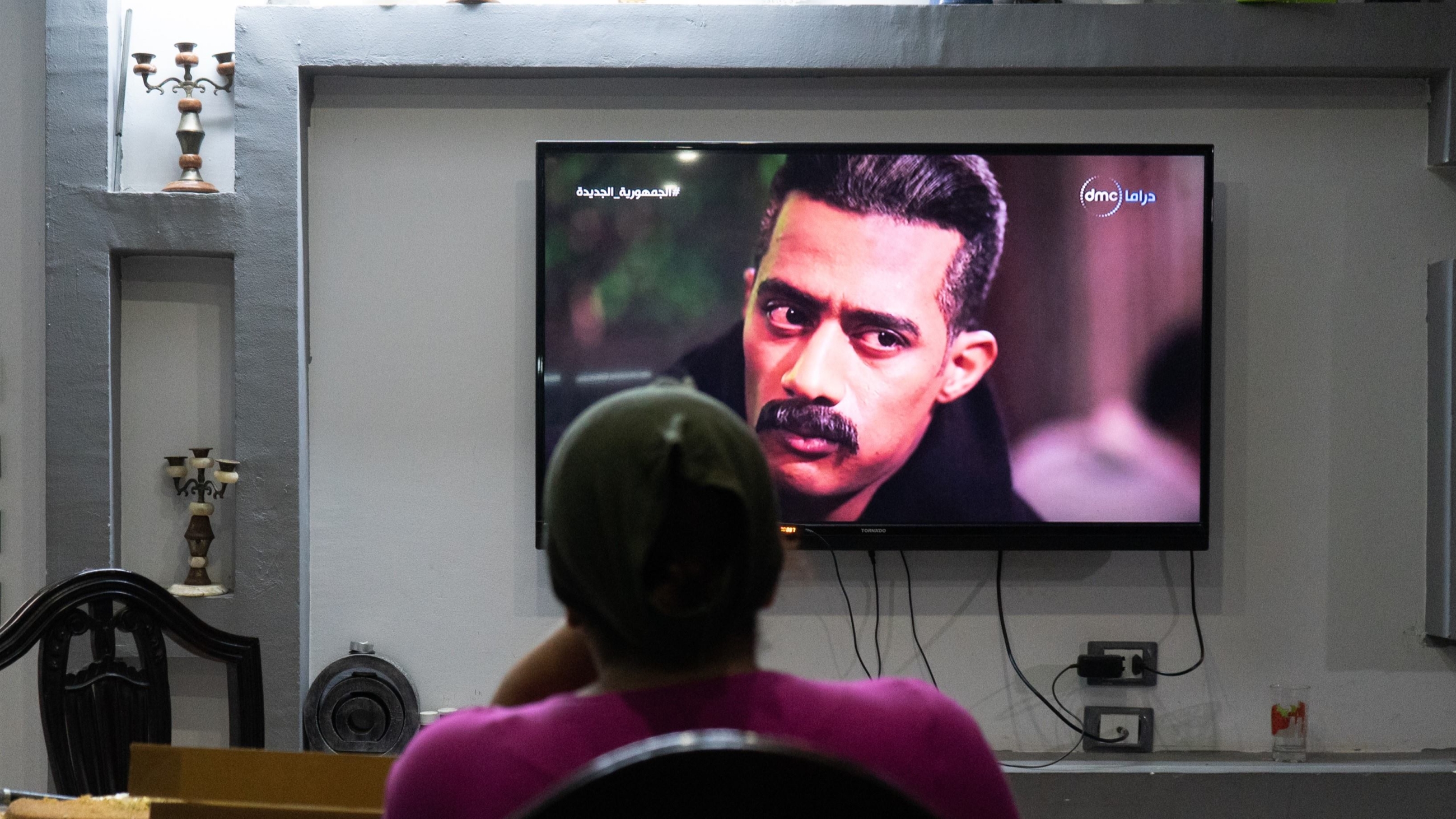

Thirty days with countless broadcasting hours and controversies; the 2023 Ramadan TV season was an intense affair, chockful of debate, scandal, and politics that reflected the state of both Arab TV and society at large.

Gaafar El Omda was the unequalled winner of the month: a rare Arab hit obsessively followed by millions. But the Mohamed Ramadan vehicle was not the only series to capture the Arab imagination.

Mona Zaki was the most bankable female star with Taht El Wessaya (Under Guardianship); the drama had a strong showing for its biggest season since the outbreak of war.

Ramadan remains the most important time of year for Arab TV, capable of uniting viewers from every demographic from every corner of the region.

Beyond creating an advertising bonanza, TV also dominated public discourse more generally as viewers sought a break from dispiriting politics and demoralising economies.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Everywhere during the month people were talking about TV: in cafes; in health clubs; at iftar and sohour parties, on portable devices on public transport; and in nearly every household.

The quality of the content and its politics is a different story, but the large viewership numbers are proof that the enduring popularity of Arab series.

So, without any further ado, here’s the lowdown on this year’s Ramadan TV offerings.

Mohammed Ramadan is still the king

There was no shortage of invincible alpha males this year: El Aghar, Baba El Magal (Father of the Domain), Souq El Kanto from Egypt; and Al Zind and Al Arbaji from Syria.

But one towered above all the rest.

After taking a more serious and arty direction with folk epic Moussa in 2021 and muddled action drama El Meshwar (The Journey) in 2022, Egyptian star and singer Mohammed Ramadan once again collaborated with Mohammad Sami – director of his two biggest hits Al Ostora (2016) and El Brince (2020) – for Gaafar El Omda.

The movie is another “shaabi” (folk) yarn about a testosterone-pumped hero trying to get even with those who crossed him.

Ramadan plays the eponymous millionaire businessman who spends the series searching for his long-lost son while struggling to tend to his four adoring wives and domineering mother.

Gaafar is a piece of "Masala" – a grotesquely epic melodrama laced with misogyny and cheap sentiment. And yet it’s compulsively watchable, helped by a largely sympathetic hero with a simple predicament.

The character is an ideal for disempowered Arab men: a rich, brave, and just man who chooses to live in his working-class district of El Sayeda Zeinab – albeit a prettified, photoshopped one– over compound life.

An Arab alpha male, but one with a sensitive side and weakness for beautiful women, Gaafar is pure fantasy, rooted in old-fashioned Egyptian drama, and imbuing the kind of street smartness most of this season’s serials lacked.

Ramadan plays the eponymous millionaire businessman who spends the series searching for his long-lost son while struggling to tend to his four adoring wives

Much ink in Arabic media has been spilled about the head-scratching popularity of Gaafar, which seemed to be everywhere this Ramadan, from endless memes shared online to crazy tribute billboards.

But its success is probably due more to the hard times that we are all living through than any magic formula that Samy and Ramadan may have unearthed.

Simple gratifications and traditional values set against a recognisable reality is all the masses want amid the worst economic crises in a generation.

Samy and Ramadan certainly did deliver in that regard, but that doesn’t take away from the crassness, ugliness, and sheer stupidity of their project.

Controversy and censorship still dominate

Controversy is a ubiquitous headline maker for the Ramadan season: from salacious celebrity secrets shared on after-iftar talk shows to tabloid gossip about production sets.

TV shows are also prime targets for MPs and conservative activists across the region.

But the Assad family-inspired drama Smile, You General seemed to generate the loudest debates on social media as regime supporters and their opponents became locked in fierce arguments.

Iraq’s Al Kasser, a rural drama about tribal conflicts and revenge crimes in the country's south, was taken off air after episode three because it was accused of “insulting tribal sheikhs”.

MBC’s Dof'at London (The London Class) was an ensemble period drama penned by Kuwaiti writer Heba Mishari Hamada about a group of Arab medical students attempting to reconcile their differences while living together.

The show was attacked for depicting Iraqi women as maids, escalating tensions between Iraq and Kuwait and forcing the latter’s Minister of Information to state that the series is not a Kuwaiti production and that it never obtained the ministry’s approval.

Sudan’s Wed El Malek (The Friendship of the King) was criticised for its unflattering portrayal of a corrupt sheikh, while Tunisia’s Fallujah was targeted by the Minister of Education for its austere representation of governmental schools.

Algeria’s drama El Damma was censured by MPs for an apparently excessive focus on drug consumption and insulting depictions of veiled women.

The severe scrutiny Arab dramas have always faced has been boosted by social media and users have normalised bullying, covert political agendas, and more censorship.

Personal attacks on creators have become the norm and government intervention is increasing. While censorship may be nothing new, the space available for creativity is still getting smaller and smaller.

Comedies suffer from inconsistency

Comedies have always been a draw during Ramadan, whether they are prank shows, sitcoms, or social comedies.

But they often suffer from inconsistent writing, and this year was no different. If anything, the writers seemed even more erratic than in previous seasons.

There were no happy returns for the new season of the Egyptian hit comedy series El Kebeer Awy.

Last year’s sixth installment was the show’s best to date – a brilliant, hysterically funny pop culture parody that touched upon everything from Squid Game to Egyptian film festivals.

But El Kebeer 7, which was scripted and filmed throughout Ramadan, was nowhere as incisive or focused by comparison, delivering a hodgepodge of sloppy writing and un-engaging plot lines peppered with a heavy-handed critique of social media that felt out of character.

The show did manage to pick up steam with the last 10 episodes, culminating in a side-splitting finale that echoed Everything Everywhere All at Once, but the series loast a large chunk of its fans along the way.

Elsewhere, veteran Egyptian actress Yousra failed to capitalise on last year’s moderately successful Ahlam Saeida (Sweet Dreams), sinking without a trace in 1,000 Hamdella Al Salama (Welcome Home), a humourless chronicle of an Egyptian family in Canada returning home to reclaim their late father’s inheritance.

Menna Shalabi’s game designer travelled to Beirut to confront relatives she suspects of seizing her property and falls in love with a married man in Taghyir Gaw (A Change of Scenery), an airy if formless wannabe existential comedy that marked the unwelcome debut of Palestinian star Saleh Bakri donning a distractingly fake Lebanese accent.

The long-running Saudi sketch show Tash Ma Tash made a comeback with a 19th season that nobody needed. Toothless and desperate for relevancy, the show’s panoramic take on the new-found changes in Saudi society no longer feel edgy or insightful.

The sole successful comedy of Ramadan 2023 was El Soffara (The Whistle), a Bedazzled-like fantasy about a down-on-his-luck tour guide who gets a second (and third and fourth) chance to turn his life around when he stumbles upon a time-travelling whistle.

El Soffara is a vehicle for Ahmed Amin, a former internet sensation turned astute commentator on middle-class mores. Having produced well-received SNL-like sketch comedies, Amin then landed the lead in Netflix’s ill-fated horror Paranormal.

Amin’s conservative middle-class ethos is the focus in El Soffara, a message-laden show that can’t resist preaching the virtues of self-love and surrendering to the Lord’s will. But Amin – a co-writer on the show – has an effortlessly comedic presence that tamps down the preachy aspect.

His comedy is fresh, razor-sharp, and truly riotous, and he is possibly the best Arab comedian at the moment, meaning watching El Soffara - in spite of its defects - was the most fun this writer had this Ramadan.

Stories of the elite are an ineffective distraction

Part of the success of Gaafar El Omda has to do with the fact that Egyptian upper-middle class stories dominated the season.

From the Cheaper by the Dozen-like comedy Kamel El Adad (Full House) and the aforementioned A Change of Scenery to marital infidelity drama Kheyana Mashro’a (Legitimate Infidelity), compound life was the default background for many of the year’s stories - and a jarring diversion from the nation’s despairing reality.

The baffling critical acclaim of El Harsha El Sab'a (The Seven Year Itch), a derivative Bergmanesque marital drama that says little to nothing new about contemporary coupling, did not translate into large ratings. Was the series too bleak for Ramadan? Perhaps.

But the conspicuous wealth paraded in El Harsha and similar shows feels increasingly infuriating and out of touch with the reality of a country where two thirds of the population live below or near the poverty line.

By contrast, the cultural impact of Mohammad Shaker Khodeir’s Taht El Wessaya (Under Guardianship) spoke volumes about the type of serious drama Egyptians want to connect with these days.

Set in the port city of Damietta, starlet Mona Zaki plays Hanan, a widowed mother of two, who is confronted by the potential loss of her late husband’s fishing ship and her children as a consequence of a 70-year-old article in the constitution that grants guardianship rights to the widows’ in-laws.

Bearing considerable resemblance in look and atmosphere to Luchino Visconti’s 1948 Italian neo-realist classic La Terra Trema, Shaker Khodeir – director of the 2016 smash hit Grand Hotel – brings an earthly poeticism to a story that does not flinch from the gruelling reality of a world still governed by steadfast patriarchy.

Khaled and Sherine Diab’s script does occasionally feel like issue-heavy television that allows its message, as worthy as it is, to trump characterisation and storytelling.

But with the controversial laws at the programme's heart now facing amendment or abolition after having been brought into parliament in the wake of the show, Under Guardianship could end up being the year’s most influential series.

The resurrection of Syrian TV raises thorny questions

Going head-to-head against Egyptian dramas in the 2000s, Syrian shows nearly vanished following the start of the war in 2011. Although production did not stop entirely during the conflict, production values did take a knock, and regional TV networks avoided broadcasting Syrian shows amid a political boycott of the Assad regime.

But with Arab governments now normalising relations with the Assad government, things are starting to change. Ramadan in 2023 saw a deluge of Syrian shows being broadcast and streamed across the region, particularly on Emirati and Saudi networks.

Along with the aforementioned vengeance fables Al Zind and Al Arbaji, there was also Dawar Shamali (A Left Turn), a social drama exploring life in Syria during the 90s amid the rise of religious fanaticism; Wa akhreeran (At Last), the story of a romance between a poor woman and an ex-convict; and Marba El Ezz, an anthology of three stories set in three different alleys.

None of these series address the reality of Syria today - a country forced into a decade-long regional isolation - and at best these productions are entertaining diversions that say nothing about the true spirit of the age.

The thawing of relations between the Assad regime and Arab leaders explains why Gulf producers are returning to Syria, which is a country with an attractive TV industry that still has the pull to draw a sizable viewership.

But while the majority of Syrian shows are apolitical and none offer a pro-Assad slant, it’s still difficult to welcome the return of Syrian drama.

Naturally, not everyone who works on these shows is pro-government, and many silenced Assad opponents who remained in the country are struggling to find their place in this rapidly changing ecosystem.

But as independent producers emerge from the ashes and regional giants head back to Syria in search of opportunities, Syrian drama will need to be closely scrutinised in the months to come.

Iraq, Tunisia and Algeria offer solid alternatives

While Egypt dominated viewership, a number of excellent new works from smaller markets in the region made for stimulating alternative programming, even if they did largely fail to attract significant viewers outside their respective countries.

The aforementioned Fallujah and El Damma were grittier, bolder, and more uncompromising in their vision than the more sanitised Egyptian and Syrian productions.

Both are informed by an anti-establishment sentiment conjured up by artists unafraid to convey the unpolished reality of their countries.

Iraq continues to make strides in TV production with two accomplished series. The first is Ekteham (A Raid), a tense thriller about a young mother pushed to raid a bank in order to fund surgery for her daughter, who has spinal muscular atrophy.

The second is Baghdad Al Gadida (New Baghdad), an inventive take on The Count of Monte Cristo about a framed journalist who is released from prison and sets off on a mission to avenge the men who wronged him.

Both works use genre tropes in weaving their multifaceted portraits of the new Iraq: a country mired in corruption, growing class disjunction, and sexism.

Both are capably made, elevated by muscular direction and solid performances, especially in New Baghdad with its star-making performance by British-Iraqi newcomer, Samya Rahmani.

Egyptian propaganda is still alive, but is anyone watching?

Egyptians were spared another installment of El Ekhteyar (The Choice), the inflammatory, history-altering propaganda show that ran for three years straight and ended in 2022 delivering a much-parodied chronicle of how Sisi saved the country from the Muslim Brotherhood.

However, military propaganda did not entirely disappear and this year saw two new programmes that were almost identical in form, characterisation and content.

The Choice: El Kateeba 101 (Battalion 101) and Harb (War) are both action-packed productions revolving around morally flawless police and military men sacrificing their lives to protect the country from the evil Islamic terrorists.

Like The Choice, both are simplistic, monotonous, and duplicitous. Unlike The Choice, both were completely ignored by a population that has lost faith in its government and the president they see as responsible for their country’s economic ruin.

At a time when disillusionment and dissatisfaction at Sisi’s catastrophic polices are reaching a new high, Battalion 101 and Harb feel like a desperate attempt by the regime to remind the people of the dangers it has safeguarded it from – a futile postscript that is out of touch with the angry spirit of the time.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.