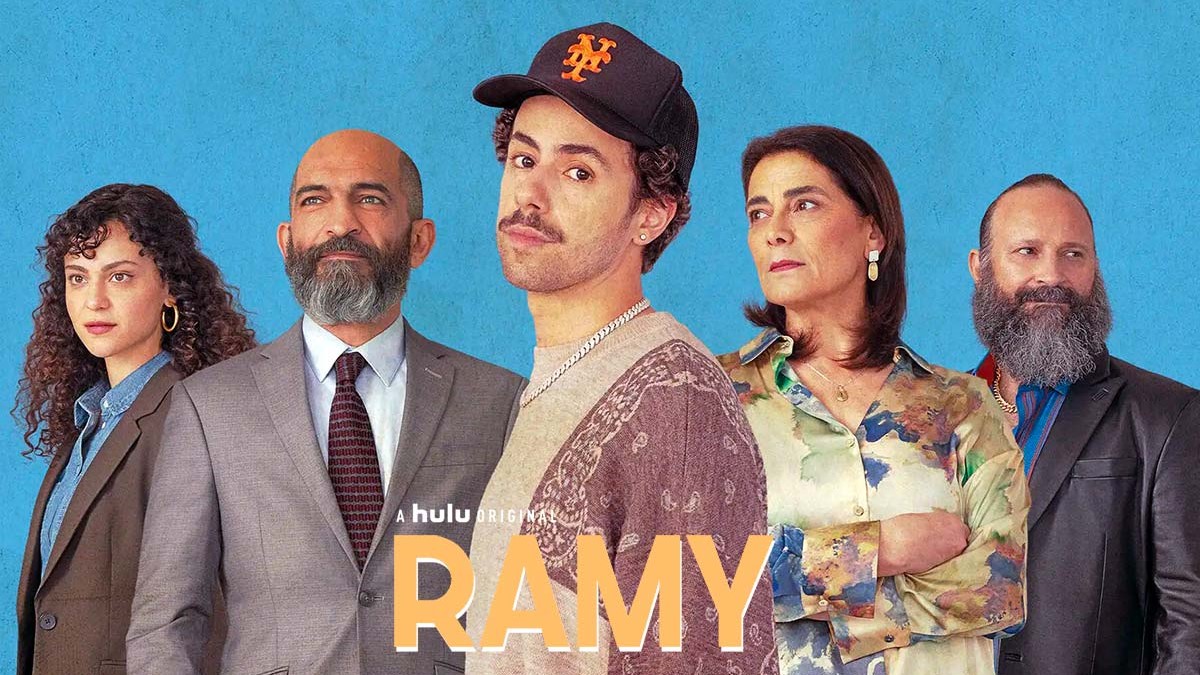

Ramy season three: Wiser, more tortured, but just as misguided

Editor’s Note: This review of the Hulu series Ramy contains spoilers

Three seasons in, Hulu’s Ramy appears to have accomplished everything it set its sights on by becoming the first series fronted by an Arab-Muslim family on American TV.

Placing Islamic mores at the forefront of American pop culture, the show reflects its Golden Globe-winning showrunner Ramy Youssef’s own spiritual journey.

This writer has previously expressed reservations about the first two seasons of the show for its stereotypical depictions of Arabs, its one dimensional female characters and the superficiality of Youssef’s conception of the "good Muslim", which boils down to pre-marital sexual abstinence.

Season three has brought improvements, including an eye opening detour to Egypt; female characters that are far more complex and a central conflict that is no longer limited to dogma and ritual but also includes relatable ethical choices.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

Nevertheless, Ramy remains a jumbled and maddingly inane affair, demonstrating a deeply confused vision that reflects its writer’s puerile thought; a product of overdosing on Martin Scorsese’s tortured Catholicism instead of an understanding of Islamic philosophy.

The show’s creators have commendably amended issues found in earlier seasons but more glaring problems arise in the latest instalment, including Youssef’s evergreen fixation with sex and his exasperatingly reductive take on Arab culture and Islam.

Setting the scene

Season three picks up where season two left off: Ramy Hassan is living with his parents again because his marriage to Zaineb (MaameYaa Boafo) has broken down following his admission that he slept with his cousin on the eve of their wedding.

Patriarch Farouk (Amr Waked) tries to reinvent himself as an entrepreneur after being made redundant in the previous season by joining his wife Maysa (Hiam Abbass) in the gig economy.

Hassan the elder has squandered most of his savings on a villa purchased in Egypt’s north coast but the man who sold him the property online has disappeared.

Left penniless, Farouk attempts to sell off anything of value in the family home from vintage French plates to their Amazon Alexa.

Maysa meanwhile struggles with the dread of ageing and the reality that her children no longer seem to need her.

Ramy’s sister Dena (May Calamawy) initially seems to have a more optimistic trajectory as she prepares for the bar exam that will fulfil her dream of becoming a migration lawyer. A reality check appears, however, in the form of a reprimand from a superior for taking on the case of an undocumented maid who is sexually harassed and fired by her employer.

Elsewhere, an Israeli-American diamond dealer recruits Ramy providing the character with a new start away from his racist uncle Naseem (Laith Nakli) who remains a closeted homosexual.

After a brief and largely unenlightening trip to Jerusalem, Ramy sets aside his qualms working for the shady Israeli dealers and gradually transforms into a successful jeweller.

Ramy’s spiritual vacuum remains, sustained by the failure of his marriage and compounded by his sexual detours with Israelis. The wealth he accumulates is unfulfilling fodder for the emptiness that continues to devour him.

Still fixated with sex, Ramy has given up on reconciling his urges with his faith, setting himself loose into a vortex of self-destruction.

A world of black and white

Though fleeting, Youssef presents a multifaceted portrait of an Arab family coming to terms with the vacuity of the American dream. No one has strong passions about anything and all of the characters go through the motions without questioning their roles as cogs in the capitalist machine.

Dramatically speaking, the characters endure little if any development from previous. Farouk and Maysa’s marital disenchantment is still simmering and Naseem’s gay dilemma remains unchanged. While Ramy of course grapples with his failure to become a good Muslim, an ideal never fully elucidated over the course of the show.

Dena stands out as the sole character with tangible growth, at least on the surface. Ramy’s younger sister is now more comfortable in her own skin; neither conflicted about her religion, nor endeavouring to fit in like her parents and uncle. She finds a temporary calling in law, a sense of purpose everyone in her circle lacks. Her family disputes will always be there but she’s more at peace with who she is.

In one highlight of the new season, Dena discusses her sexual awakening with her therapist, asserting that she is free of her brother’s hang-ups.

“That sexual feeling made me feel like a woman,” Dena says, revealing that she took it as a means to embrace and accept her womanhood.

In one segment she sleeps with a naive immigrant Egyptian physician her mum found for her on a dating app before finding out he was a virgin. In a reversal of gender roles, Dena finds herself obliged to comfort the man but isn’t really remorseful.

Though tamped down, Ramy remains fixated on sex; Dena must deal with the uncalculated consequences of her night with the Egyptian and Naseem can’t bring himself to come out.

Ramy, meanwhile, suffers from erectile dysfunction (presumably because of his lingering self-reproach over the divorce), before confining himself to an older Latin sex worker, as according to his Orthodox Jew colleague, it’s less sinful being sexually monogamous.

More compelling are the ethical conundrums the show confronts its characters with. In a brief but worthwhile departure from sex, guilt has been extended to everyday moral melees: Ramy inadvertently puts a Palestinian child in Israeli detention while Dena gives false hope to the undocumented maid.

Nearly every character is forced to make difficult moral choices, as idealism and reality are constantly pitted against one another. And for the most part, reality wins. It is to Youssef’s credit that he puts his characters through the wringer, enriching the drama and giving it more weight.

Yet these enhanced moral conflicts are undermined by the contrived links he forges with Islam, in his obsessive search for the Muslim ideal. These new lines of conflict eventually come off as obvious ploys to expand Islamic guilt beyond sex, which was the case in seasons one and two.

In Ramy’s world, everything remains black and white. Moral choices may be mired in greyness, but they’re always solidly delineated.

To atone for their disagreeable choices, the protagonists subject themselves to physical pain: be it when Ramy asks the sex worker-masseuse to hit him, or when Dena joins the maid in cleaning a flat.

This form of self-flagellation is common in Christianity but not in the Sunni Islam at the heart of the show. Self-flagellation is nowhere to be seen in the religiously minded Middle Eastern films and series tackling guilt, for example.

The form is familiar in pop culture through the Catholic iconography of Martin Scorsese whose stories are deeply rooted in his childhood experiences. Youssef borrows this symbology and shoehorns them into a Muslim context, but the end result is not only derivative, it’s disingenuous.

Tired stereotypes

Equally disingenuous and tiresome is the cliched portrayal of Arabs - an issue the show has not eradicated throughout three seasons. The latest includes the trope of the Egyptian virgin wanting to marry Dena after having sex with her for the first time, and the young Palestinian tinder match with a penchant for quoting Chomsky to the increasingly ignorant Maysa.

Most infuriating is Hanan (Ahd Kamel), the traditional young Saudi mother who approaches Ramy’s married friend Ahmed (Dave Merheje) to become his second wife after her terminally ill husband dies.

At one point, she brags: “I’m Saudi. I’m rich," implying that being rich is a birthright for Saudis.

Hanan is another instance of Ramy’s disparaging depiction of Gulf nationals. Another example was the Emirati Sheikh Bin Khalied from season two, who has a fetish for breastfeeding.

There’s also representation by omission in the case of marginalised Coptic Christians, one of the biggest and oldest Arab communities in Ramy’s Jersey hometown.

For all its wide assortment of Arab and Egyptian characters, Ramy, over the course of three seasons, seems not to have met a single Arab Christian in his life, be it in the US, Palestine, or Egypt, cementing the misconception that the Arab world is one monolithic entity. In addition, secular Arab Muslims, who have been conspicuously absent from season one, also continue to have a no-show in season three.

Ramy’s plotline in Jerusalem and his normalised relations with the Israelis is equally problematic. The show’s fundamental discourse on the Israeli-Arab conflict is superficial and oversimplified. In one scene, the Orthodox Jewish diamond dealer tells Ramy, “"Over there (the occupied territories) we have conflicts. But over here (New York), we're like brothers.”

The show frames the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as an extraneous phenomenon outside Ramy’s scope of comprehension, advocating a fake version of a harmonious co-existence.

In contrast to his relations with Jewish characters, Ramy feels alienated from the Palestinians he meets in Jerusalem, first by the much smarter Tinder match and then by the bullying boys he gets in trouble with.

A rude awakening comes in the form of his connected Israeli business partner who does not act on her promise to save the unlawfully detained child. Still his concern about the issue stems from personal guilt over his role in the incarceration rather than the inherent wrongs of the situation Palestinians live through.

On Sisi's Egypt

Ramy fares considerably better when it turns attention to Egypt. In the season’s best episode, Farouk goes back to his birthplace to find the swindler who sold him a rundown North Coast villa.

In one 30-minute episode, Youssef introduces the viewer to Sisi’s neo-liberal Egypt: the proliferation of American culture, the decentralisation of Cairo and the construction of uninhabited luxury housing.

Also explored is the expatriate Egyptian’s attraction to economic opportunities in the country, which always proves to be a mirage, as well as the sexual liberation of its youth with a plotline following Farouk help an unapologetic woman seek an abortion.

Ramy is far more interesting on Egypt than on Islam or the contemporary US. Farouk and Maysa represent a generation of Arabs who neither achieved the financial prosperity they left their home countries for, nor managed to integrate themselves into American society.

In one of the few nuanced scenes of the series, Farouk, intoxicated on mushrooms, tells Maysa: "We're visitors,” to which she replies: "We've been here for 35 years."

One wishes the focus of the series would have been Farouk and Maysa, or perhaps Dena, but Ramy is foremost a chronicle of Youssef, and that is the story’s biggest Achilles' heel.

An 'unexamined' philosophy

The latest season starts with a famous epigraph courtesy of Socrates, who states “the unexamined life is not worth living”. That is followed by a voice over from Youssef who asks:

“Do you believe in fate? How can you choose what's already been chosen?”

Youssef ventures to explore the ancient debate around predetermination and free will.

“Even though everything is planned, there must be a choice,” he says later in the series. At the end of course, by divine intervention, his God gives him the clues he aches for to make a choice.

“God chose,” he finally declares at the end of the series.

Youssef’s self-described spiritual journey feels like someone who read Sophie’s World and listened to a couple of podcasts, and felt confident enough to present a philosophical treatise on the subject.

The show’s approach to this ancient dilemma is dated, reductive, and, to be blunt, downright vacuous. Youssef ignores centuries of thought - from the Greeks to enlightenment thinkers - while also showing no concern for classical and modern Islamic philosophy and their interpretation of scripture and investigations into the role of religion in modern societies.

Youssef tackles theology head-on and makes it difficult for a thinking person engaging with his ideas not to question the complex dimensions he leaves out.

For all its seemingly progressive sentiment, at the end Ramy shows its true colours: this is a dumb, regressive, and occasionally offensive American comedy that wants to have its cake and eat it.

Dena gains control of her agency, yet in the finale, she defies all logic and opts to marry the Egyptian ex-virgin instead of fighting for her place in the American legal system.

Ramy deems sex outside marriage to be spiritually damaging and unfulfilling, asserting that his best was with ex-wife Zainab and only finds contentment and peace with the daughter the latter has hidden from him.

Ramy has presented an insultingly restrictive and uniform picture of Arabs and Muslims

His notion of happiness can only be achieved through traditional family structures, a notion further emphasised by his parents.

Towards the end Farouk exclaims that he and Maysa have endured suffering, “selling our souls for hot dogs”; their pursuit of the American dream comes at the cost of what matters.

But what does matter?

That’s a question the series leaves unanswered.

Do we reach peace and happiness through constructive and healthy marriage? Through detachment from earthly pleasures a la Buddhism or Hinduism? Or through useful work? We never learn.

As a result, the question that begs an answer is: who is Ramy for exactly? On one hand, it feels like a show catered to a white American audience with its excessive exposition and explanations of Islamic rituals and norms.

On the other, the series is replete with too many Arabic inside jokes and references that go over the heads of the same white American viewers - from the Palestinian kid calling Ramy “the American Limby”, referencing Mohamed Saad’s infamous dimwitted Egyptian character, to the joint casting of Waked and Khaled Abol Naga, Egypt’s dissident film stars, who have been living in exile for years, in one episode.

The show is certainly not for viewers seeking honest insight into the multifarious dynamics of Arab and Muslim lives. Throughout the course of its three seasons, Ramy has presented an insultingly restrictive and uniform picture of Arabs and Muslims engineered by a showrunner with an alarmingly limited and homogenous worldview.

Ramy is nowhere as authentic and honest as it likes to think it is, and it doesn’t come close to capturing the immensity and density of the Arab and Muslim experience.

The Arab experience in the West - be it Muslim, Christian, Jewish, or secular - deserves better treatment.

Ramy Youssef, with his confused, infantile ideology and increasingly self-indulgent screen presence, is not the artist to convey it.

If season 3 ends up being the show’s last, which is probably not the case, this writer will certainly not miss it, for the harm Ramy does far outweighs its virtues at this stage.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.