The fate of the Moriscos: The last remnants of Islam in Spain after the Reconquista

It’s an unfortunate reality for Spain and the Islamic World that the late dictator Francisco Franco’s adage that “the Arabs came, then they left” is taken as fact.

The statement serves as a lexical axe on the impact of Islam in Spain and its presence in the Iberian peninsula, which spanned over 800 years.

Not only does this actively conceal the lives of Muslims during the epoch of Al Andalus, it does not account for their lives after the conquest of Granada, the last Muslim Emirate, in 1492.

The closing stages of the Reconquista, or the Christian reconquest of Islamic Spain, coincided with the Inquisition, an institution within the Roman Catholic Church that was sanctioned by the Spanish crown and aimed to root out heresies threatening the Christian faith in Iberia.

Preceding the fall of Granada, the Treaty of Granada of 1491, signed by Ferdinand II and Isabella I and Muhammad XII of Granada, ostensibly guaranteed freedom of religion and forbade any attempt to forcibly convert Muslims, in return for submission to the Spanish crown. However, the agreement was never enforced.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

For Muslims and Jews, newly subject to Christian rulers, this ultimately meant a campaign of forcible conversion to Catholicism, with Jews who refused to convert being forced into exile in 1492. Muslims were subject to numerous purges, culminating in the final expulsion in 1609, under King Philip III, of even those who had nominally converted to Catholicism.

So what happened to the Muslims who silently witnessed the tragedy of the Inquisition? What were their lives like after they were forcibly converted?

Purity of blood

The first clue lies in the word used to describe those Muslims who converted to Christianity.

Morisco in Spanish means “little moor”, and refers to former Muslims and their descendants who were forced to change their faith by the Inquisition.

The use of morisco shows that these new Catholics could not entirely relinquish their past religious affiliation, and that their outward conversions did not undo the reality of their “Moorish” or Muslim origin.

This distinction has its roots in the idea of limpieza de sangre or “purity of blood”, which developed in Christian Spain in the late 14th and early 15th centuries and was used to target recent Jewish converts to Catholicism, who were known as conversos.

The doctrine ignored the fact that many Spanish Muslims were the offspring of intermarriages between Arabs and Amazigh conquerors and native Iberians, and were also often Christian Iberians who had converted to Islam.

Mass Jewish conversions to Christianity had occurred forcibly and through coercion throughout the period, and suspicion lingered among the “old” believers that these newcomers to the faith were not sincere.

This led to the persecution of the Conversos, culminating in a series of discriminatory statutes by the Council of Toledo in 1449, which banned members of such communities from holding public office, doing certain jobs and even marrying into “old” Christian families.

Similar suspicion was applied to Morisco converts after the fall of Granada.

The fact that many Jewish and Muslim converts to Christianity continued to practise their original religions in secret did not help dispel such suspicions.

Others, though, may have become sincere believers in Christianity, and unfair victims of the suspicion created by their co-religionists.

This departure from the concept of Christian brotherhood may have had its roots in suspicion about the new converts’ sincerity but also in temporal interests.

Former Jews and Muslims who changed faith represented economic competitors, as their new religious affiliation meant they could not be discriminated against on the basis of faith. Ancestry, though, represented an unchangeable basis for hatred of the other.

Families did not hold complete versions of the Quran, but instead, pages of surahs (chapters of the Quran) were scattered around their home in order to evade detection

Such burgeoning prejudices may also have merged with early examples of racially motivated discrimination.

The historian María Elvira Roca Barea proposes the “Placate Europe” hypothesis, which says that Spaniards were usually met with open suspicion and contempt by the rest of Europe during this period for “having dirty blood”, and the image of Spaniards being the progeny of “Jews and Moors” tarnished the Spanish crown’s desire to propel Spain to the forefront of world politics and power.

King Ferdinand II and Queen Isabella's decision to promote the idea of purity of blood legitimised discrimination against Spaniards of Muslim heritage, even if they had converted and even if they were in fact predominantly of “Iberian descent”.

The second major hypothesis, proposed by historian P Boronat, was the “Ottoman Scare” theory, which suggested that the presence of “fifth column” Moriscos on the Iberian peninsula would invite invasions from the Ottoman Empire - a potent threat after the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Crypto-Islam

There is evidence that Moriscos genuinely believed in Islam even as forced conversions increased after the fall of Granada.

The practice was clandestine and the Moriscos would soon be painted by historians as crypto-Muslims.

To help ease the conflicting demands of their inward belief in Islam and their outwards practice of Catholicism, Muslim scholars in neighbouring lands issued rulings allowing Moriscos to hide their faith.

Mufti Ahmad ibn Abi Jum'ah’s Oran fatwa is one notable example and was mandated by the Zayyanid Kingdom of Tlemcen - now modern-day Algeria.

The fatwa itself did not refer to the Moriscos by name, in order not to draw attention to the advice presented, and instead referred to il-guraba (those from abroad).

However, given the publication of the fatwa during mass conversions in Spain, it is evident who its subjects were.

The ruling affirmed the regular obligations of a Muslim, including ritual prayer (salat) and charity (zakat). However, these obligations could be fulfilled in a relaxed manner, such as praying through “making slight movement” and zakat (alms giving) through “generosity to a beggar”.

Muslims were also allowed to contravene strict Islamic taboos, for example consuming pork and wine, if their lives were at risk. This tactic was a frequent method of the Inquisitions enforcers, who would make travellers eat pork or blaspheme against the Prophet Muhammad.

Interestingly and ironically, one of the four known surviving manuscripts of this fatwa can be found in the Borgiano Collection in the Vatican Library.

Primary sources also attest to the practice of Islam by Moriscos who were outwardly Christian.

The writings of a 16th-century Morisco author, known cryptically as the “Young Man of Arevalo”, included accounts of clandestine Muslims and descriptions of their religious practices.

For example, families did not hold complete versions of the Quran, but instead, pages of surahs (chapters of the Quran) were scattered around their home in order to evade detection.

Another 16th-century story attests to the existence of La Mora de Ubeda, a 93-year-old illiterate Morisca woman who was renowned for her extraordinary oral knowledge of the Quran, revealing the health of crypto-Islam during the time of the Inquisition.

The exodus

The Moriscos' fate was sealed by a mixture of doubts over the sincerity of their conversion and fear of their posing a threat.

After just over a century of Christian rule, in the early 17th century, King Phillip III ordered the expulsion of Moriscos from Spain.

In 1612 an eyewitness, Pedro Aznar Cardona, an apologist for the expulsion of the Moriscos, wrote about their forced exodus in Valencia, describing people “bursting with grief and tears, amid a great uproar and confused shouts”.

He paints a bewildering landscape of women, children and the elderly who looked back on their abandoned homes as they were cast adrift to foreign lands.

Matthew Carr, historian and author of Blood and Faith: The Purging of Muslim Spain, 1492-1614, wrote: “they [the Moriscos] were marginalised and persecuted for more than a century before the Spanish state decided they were incapable of becoming ‘good and faithful’ Christians - but they still considered themselves Spaniards even when they were dumped on the beaches of North Africa”.

The Inquisition targeting Muslims and Moriscos lasted almost 350 years and was characterised by mass conversions, violence and sociocultural decline, as many Muslims were force-fed pork to prove their Christianity, had their Qurans desecrated, and their places of worship destroyed or converted into churches; most of the main cathedrals of each city in Andalucia, such as that of Sevilla or Cordoba, were at one point functioning mosques.

After Phillip III's edict in 1609, many of the crypto-Muslims who stayed on largely went under the radar of the Inquisition.

Evidence that Islam was practised long after the expulsion includes the mass persecution of crypto-Muslims in Granada in 1727.

The lives of crypto-Muslims in this part of Spain were largely uninterrupted, so much so that they garnered significant wealth through land ownership and agriculture.

However, the ultimate impact of being forced underground, and centuries of gradual intermarriage, was that Arabic and Islam slowly died out. By the middle of the 19th century Islam as an indigenous feature of the Iberian peninsula ceased to exist.

Legacy

The genetics of modern-day Spanish populations may include evidence of the Muslim presence in Iberia.

Genealogists estimate that most Spaniards share between one and 10 percent of their DNA with their North African neighbours. That may be explained by reasons that predate the Moorish invasion of the early eighth century, such as shared Roman rule, but may also suggest that descendants of the Moriscos still walk the Iberian peninsula.

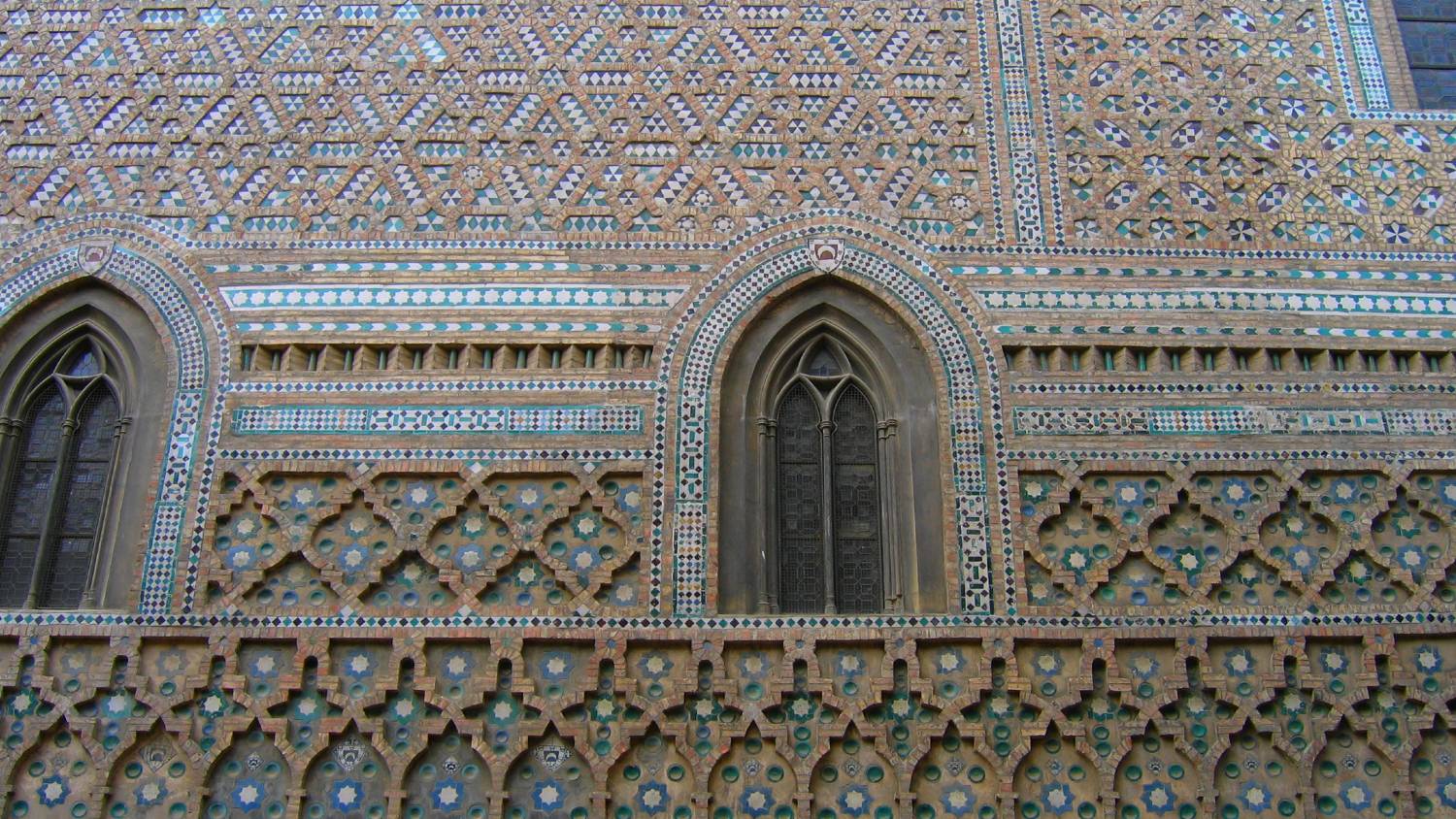

Moreover, the mark of Islam and the Moriscos is seen in the architecture, culture and cuisine, especially in Andalucia, particularly through Mudejar art, which is craftsmanship and tilework - ironically, sanctioned by the Christian elite in the time of the Inquisition.

The word “Mudejar” comes from the Arabic mudejjan, meaning “subjugated or tamed”, or al dajjan, meaning “those who stayed on”.

Some regions of southern Spain have also preserved Arabic words in their vernacular, such as arua for come here, or the custom of praying towards el levante (the levant, East), particularly in the town of Riopar in Albacete.

Today, the topic of reinstating Spanish citizenship to the descendants of Moriscos remains controversial in the country, especially since some descendants of Spanish Jews are entitled to Spanish citizenship on an expedited basis. Such programmes come with the condition that an applicant has maintained Spanish traditions, such as speaking the Ladino language - a dialect of Spanish spoken by Sephardic Jews.

Mansur Escudero, head of the Islamic Commission of Spain, explained the need to introduce similar citizenship laws for descendants of Muslims by way of “not only legal reparations but also sentimental ones, as well as historic justice”.

There has been support from the parliament of Andalucia, however the policy has not gained broader support.

Spain was, and has always been, perceived as different, a land of extremities, where historians have consistently echoed that the Arabs “came and left”, either through their indolence or active attempts to conceal Islamic history. In reality, the legacy of Islam, and Moriscos themselves, never actually left.

This sentiment is poignantly emphasised by academic Saadane Benbabaali, who claims his ancestors are Moriscos who were exiled into Algeria: “Andalucia is a world that belongs to the past, but this past had a reputation and an impact on the people who experienced it and left behind a culture, music and ideas that still exist today.”

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.