Abdulmecid II: Artist, musician and the last caliph of Islam

A talented pianist and cellist, and an artist just as comfortable depicting nude scenes in harem courtyards as he was painting the gates of mosques, the Ottoman prince Abdulmecid was the quintessential Turkish renaissance man.

There was also one major string to his bow, an accomplishment for which his name will forever be etched in the annals of history; that of being the final officially recognised Muslim caliph.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

When the parliament of the Turkish Republic eradicated the last vestige of Ottoman power in 1924, stripping Abdulmecid of the title, they would bring to a close an institution that was established by the Prophet Muhammad’s friend and successor Abu Bakr.

But history would be cruel, reducing Abdulmecid, the last figurehead of the Ottoman dynasty, to a mere footnote.

Looking out over the Bosphorus, Istanbul’s Sakip Sabanci Museum is hosting an exhibition aimed at shedding light on the life and works of the Ottoman shahzade (prince).

Running until 1 May and titled The Prince’s Extraordinary World: Abdulmecid Efendi, the exhibition features 60 paintings by the prince and 300 historical documents relating to his life.

The collection is on public display for the first time since the prince’s death in Paris in 1944.

Just as important as the artistic merit of each work, is what they demonstrate about the synthesis of European and Islamic cultures the Ottomans had managed to create by the late 19th century.

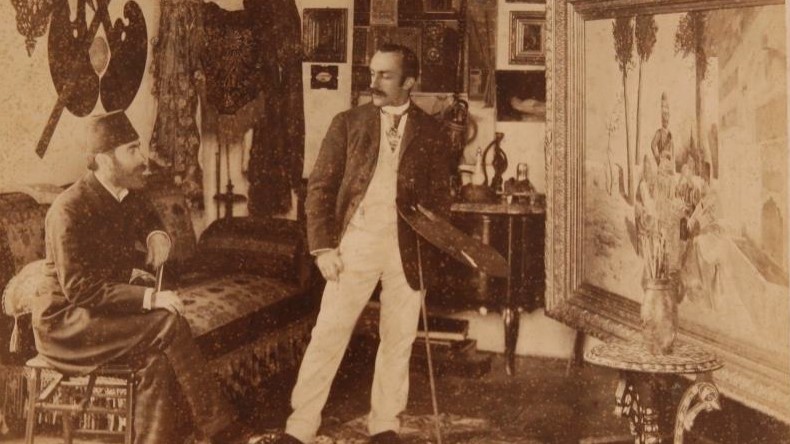

In many ways, Abdulmecid was the personification of that trend; typically dressed in the manner of a French monsieur, with a regally placed fez signalling his Ottoman roots, he was a man as comfortable in the midst of European aristocracy as he was being the heir to the last Islamic caliphate.

Early influences

Abdulmecid was born at the Beylerbeyi Palace on the Asian side of Istanbul in 1868, in what was more or less a gilded cage.

Suspicious of court intrigues and potential challenges from rival princes, Sultan Abdulhamid II, who took power in 1876, made sure that his relatives had no authorisation to act freely.

These restrictions had an unintended consequence for Abdulmecid’s intellectual development.

With little else to do, it allowed the young prince to indulge in every intellectual and creative curiosity he had, with languages and western art developing into particular passions.

Abdulhamid had opened a school within Istanbul’s Yildiz Palace, which princes and other Ottoman nobles, such as the Sharif of Mecca’s sons, could attend.

There, Abdulmecid II received education from both Turkish and French teachers, with the latter having an observable influence on his future taste and styles.

For much of the prince’s youth, the thought of one day taking up the office of Caliph was a near impossibility. Abdulmecid was low down the pecking order, as far as the line of succession was concerned.

The lack of distraction, in terms of court politics, meant he was free to focus on his love of the arts and music, as well as on his philanthropic work making contributions to causes as diverse as the Red Crescent and the Armenian Women's Association.

Nazan Olcer, the curator of the Sakip Sabanci exhibition says: “As of the 19th century’s second half, the Ottoman Palace was exposed to western art, including painting. Abdulmajid II’s father, Abdulaziz, was also a painter and established Turkey’s first painting school, sending students to receive their art education in Europe.”

Even after Abdulhamid was deposed in 1908, Abdulmecid stuck to the arts, using the freedom afforded by his cousin’s fall from power to further indulge in charitable activities, patronise museums and organise meetings of poets and painters.

As Caliph of Islam

Abdulmecid’s rise to the caliphate came as a result of the Ottoman Empire’s post-First World War demise.

In the aftermath of the Ottoman defeat and the threat of imperial powers carving up the traditional Turkish homelands in Anatolia and the Balkans, the prince pledged his support to Mustafa Kemal Ataturk and his Ankara government.

Rising republican fervour led to the abolition of the Ottoman sultanate, the end of the monarchy and the exile of Abdulmecid’s cousin, Sultan Mehmed Vahideddin (Mehmet VI).

What remained was the ceremonial and now elected position of caliph, who was to be elected by deputies of the Grand National Assembly and would be a purely ceremonial role.

It was in this context that Abdulmecid was elected caliph, the final recognised political leader of Sunni Muslims across the world.

Despite being caliph in name only from November 1922, Abdulmecid would flaunt the symbolic power of his office, riding his white horse on the streets of Istanbul in a defiant display of the Ottoman’s historic supremacy.

He also held lavish receptions in the manner of Ottomans of old and personally attended Friday prayer ceremonies at the Hagia Sophia mosque, demonstrating his leadership of the world’s Muslims.

These transgressions, whether intended to or not, would draw the ire of the anti-monarchist movement. The Ankara government did not like a caliph who appeared everywhere, saluted crowds and behaved like a sultan.

The republicans would eventually abolish Abdulmecid’s office and exile the caliph and every other member of the royal house.

When that moment came in March 1924, the royal household was given three days' notice and it was towards Europe that Abdulmecid went.

The culture shock would have been mitigated by the fact that the prince spoke French like a native, studied German for eight years and understood English, in addition to his knowledge of Arabic and Persian.

A European Ottoman

Abdulmecid and his family first moved to Territet, a small town in Switzerland, and then to the French city of Nice, where he lived until 1939 before moving to Paris.

Despite his Istanbul upbringing, European trends had been formative in the prince’s artistic and intellectual development.

Nazan Olcer, the curator of the Sakip Sabanci exhibition, said that the prince “merged the West and the East, spent his life in accordance with the zeitgeist, adhered to tradition and religion but at the same time remained open to the West.”

While Abdulmecid was unusual in enjoying both a productive career as an artist and briefly as a statesman, his journey reflects his country’s own story of modernisation and westernisation.

It was a transformation that would ultimately prove fatal to the Ottoman Empire, as the shift sparked unending debate in Turkey about whether the elites had become alienated from their own culture - a question that persists to this day.

Nevertheless, the prince was a two-winged intellectual. Olcer explains that “he was both a painter and a hattat (Islamic calligrapher).”

“He was loyal to his religion and to tradition but also a western musical performer; a supporter of theatres.”

This contrast is best represented in his nude harem painting, which unlike the fantasised depictions of western artists, presented calm family life, according to Olcer.

Addressing conservative shock and the discovery of the nude works, Olcer explains that they were by no means the main focus of Abdulmecid’s art.

“As far as we know, he has only two nude paintings: Women in the Courtyard and Roses of May,” Olcer says.

“The former is more like an etude, while the latter is a copied version of Charles Chaplin’s tableau, which used to be (displayed) on the Dolmabahce Palace’s wall. So, we can by no means call him a nude painter.”

Such debates overshadow the rest of the prince’s works, Olcer added.

In exile, Abdulmecid took up photography, capturing images from across the continent while maintaining his relations with Muslim communities, especially with those living on the Indian subcontinent.

In the first years of his exile, he also contacted Indian Muslims who had strongly opposed the abolition of the caliphate, including a sympathetic Aga Khan.

Abdulmecid’s health began to fail after the outbreak of the Second World War, forcing his move to the French capital, where he would die in 1944.

A request to bury the prince in Istanbul was rejected by the republican government and after ten days at the mortuary of the Paris Grand Mosque, the last caliph of Islam was buried in Medina - the city where the position was established 1300 year earlier.

The exhibition “The Prince’s Extraordinary World: Abdulmecid Efendi” is open now at Istanbul’s Sakip Sabanci museum and will run until 1 May

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye edition

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.