The 'Trojan Horse affair' explained

In 2013, a letter was sent anonymously to local officials in Birmingham purporting to expose a conspiracy by Islamists to take over schools in the English city.

The letter purported to be evidence of a "Trojan Horse" plot to introduce conservative Islamic rules and indoctrinate students in anti-western, fundamentalist ideologies at a number of schools in predominantly Muslim areas of Birmingham.

Stay informed with MEE's newsletters

Sign up to get the latest alerts, insights and analysis, starting with Turkey Unpacked

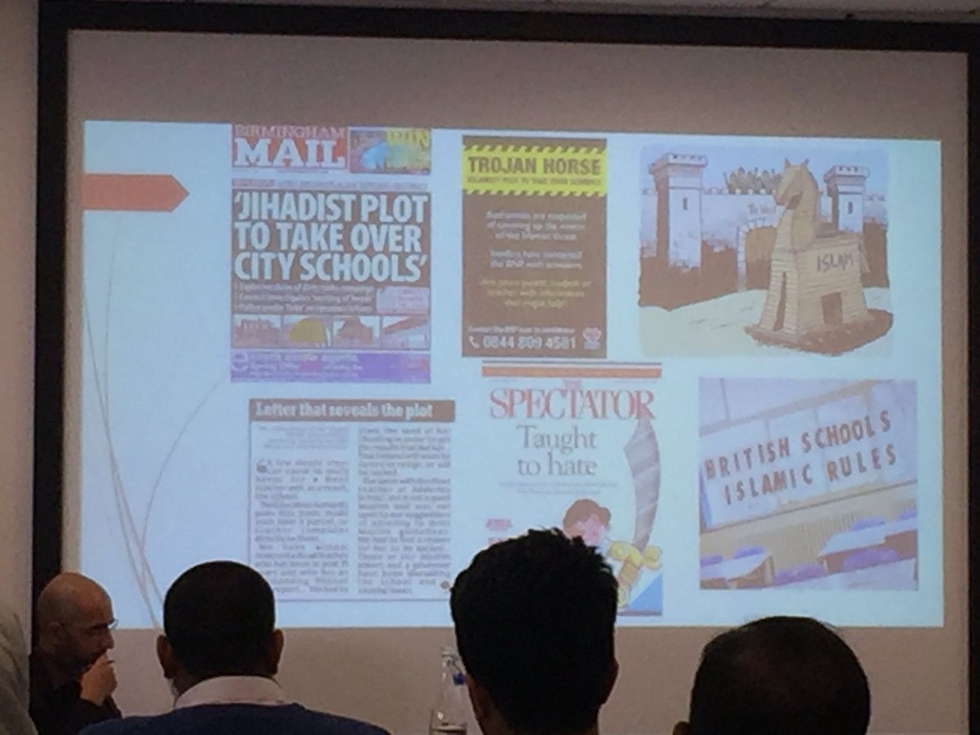

The exposure of the letter sparked a firestorm in the British media and political circles, which led to dismissals, investigations, accusations of Islamophobia, changes to counter-terrorism policy, and scare stories about the threat to secular education in the UK.

There was just one problem: the letter was almost certainly a fake. Neither the author of the letter nor the person who passed it on anonymously to Birmingham city officials has ever been identified.

Now a mammoth podcast series from the New York Times and Serial Productions is set to investigate the source of the letter and examine its impact on community cohesion and Islamophobic sentiment in the UK.

The Trojan Horse Affair, hosted by Brian Reed and Hamza Syed, and set to be launched on Thursday, promises to shed new light on the saga and determine, according to a press release issued ahead of the series, whether "an entire country has been duped".

With brand new details on the affair due to be revealed, Middle East Eye takes a look back at the details behind one of the biggest controversies affecting British Muslim communities in recent years.

How did the scandal begin?

Birmingham has long been at the heart of discussions around multiculturalism in the UK, having one of the largest non-white British populations of any city in the country, much of it descended from Bangladeshis, Pakistanis and Indians who emigrated to the UK in the decades following the Second World War.

Some areas of the city, notably the Alum Rock suburb where several schools named in the Trojan Horse letter are located, have predominantly Muslim populations.

In November 2013, Birmingham City Council received a photocopy of a letter that appeared to outline a five-step strategy called "Operation Trojan Horse", which proposed capturing Muslim-majority schools in Birmingham through a campaign targeting governing bodies, parents and staff, in order to introduce an ultra-conservative Islamic agenda.

"I have detailed the plan we have in Birmingham and how well it has worked and you will see how easy the whole process is to get the head teacher out and your own person in," the letter read.

The letter was passed to the Department for Education (DfE) in December that year, before being leaked to journalists in early 2014. Headlines soon warned of a "school jihad plot".

"Revealed: Islamist plot dubbed ‘Trojan Horse’ to replace teachers in Birmingham schools with radicals" blazed one in the right-wing Daily Mail.

Before long, the DfE and Ofsted, the school regulatory body, got involved, with the latter carrying out emergency investigations in 21 Birmingham schools.

Eventually, however, the investigations ended up focusing primarily on three secondary schools, Park View, Golden Hillock and Saltley (all three controlled by the Park View Education Trust), and primary schools Oldknow and Nansen.

What happened?

All five schools were downgraded by Ofsted following their emergency inspections in May - despite the fact that in 2012 Ofsted had ranked Park View as “outstanding”, the first school in the country to achieve the top grade under the supposedly tougher regime brought in by then-Education Secretary Michael Gove.

Initially, in fact, Ofsted recommended that Park View retain its "outstanding" rating, according to a document leaked to The Guardian, but this decision was rapidly reversed and it went from having the highest possible rating to the lowest possible rating overnight.

The management of all the schools was replaced and disciplinary proceedings were opened.

The Conservative-led coalition government quickly moved to respond to the furore: Prime Minister David Cameron convened a meeting of an extremism taskforce to discuss the affair and Gove dispatched Peter Clarke, the former head of the Metropolitan Police's counterterrorism command, to investigate the alleged plot.

Clarke's report, released in 2014, said there was "no evidence to suggest that there is a problem with governance generally", nor any "evidence of terrorism, radicalisation or violent extremism in the schools of concern in Birmingham".

Professional misconduct cases were brought against just 12 teachers, and the charges were listed as 'undue religious influence'. These cases collapsed in 2017

Nevertheless, it said there was "evidence that there are a number of people, associated with each other and in positions of influence in schools and governing bodies, who espouse, sympathise with or fail to challenge extremist views".

It said there had been "co-ordinated, deliberate and sustained" attempts "by a number of associated individuals, to introduce an intolerant and aggressive Islamic ethos" into "a few schools in Birmingham".

Eventually, professional misconduct cases were brought against just 12 teachers, and the charges were listed as "undue religious influence". These cases collapsed in 2017 after the repeated failure of lawyers acting for the DfE to share crucial evidence from the Clarke report and, in the end, only one person received a disciplinary sanction over the whole affair.

How valid were the concerns?

The fraudulent nature of the original letter notwithstanding, there has been much debate over the extent to which the document reflected genuine concerns at the schools.

Few deny that the schools controlled by Park View Educational Trust saw a gradual introduction of more overt Islamic themes, but advocates say this process reflected the faith and served the education of the Muslim-majority students attending the schools, and was implemented with the consent and approval of local and educational authorities.

Schools in the UK, which is not a secular state, are required by law to provide a collective act of daily worship which should be “wholly or broadly Christian in nature” unless they are granted a specific exemption. (In practice many schools ignore this, however.)

'If what is going on is a combination of incompetence, politicians saving their skins and sacrificing the Muslim community - that's a really important story'

- John Holmwood, academic

Park View had, in the early 1990s, first applied to have its daily worship be of an Islamic rather than Christian nature, citing the fact that the majority of the pupils were Muslim. Prayer rooms and charts listing prayer times were also introduced.

There has also been evidence from former staff members - much of it disputed or unsubstantiated, however - about specific incidents involving staff or students expressing socially conservative or sexist and homophobic attitudes.

What has been basically accepted, however, is that the claims of a city-wide conspiracy to transform the culture of Birmingham's school were bunk and what they were accused of was hard to explain in a way that made it seem uniquely reprehensible in a country where faith schools and academies freed from local government control are commonplace.

"All the stuff about extremism, it drops to being 'undue religious influence' and becomes the charge against the teachers at the tribunals," said John Holmwood, co-author of Countering Extremism in British Schools? The Truth about the Birmingham Trojan Horse Affair.

"What's the measure of undue religious influence versus due religious influence? That's where Clarke can provide no guidance."

What was the impact?

Critics have argued that the Trojan Horse affair had a disastrous impact on community relations in the UK and helped stoke Islamophobic sentiment to new heights.

In addition, Holmwood argued that it provided a basis for the British government to ratchet up counter-extremism policies, particularly the controversial Prevent duty, part of the government's counterterrorism strategy, which requires teachers, doctors and other public sector employees to report signs of "radicalisation".

In 2015, the government launched a new counter-extremism strategy, which placed a statutory duty on education and health bodies to have “due regard to the need to prevent people from being drawn into terrorism".

It specifically cited the Trojan Horse affair under the heading "Evidence of extremism in our institutions".

"If the story is a false story, if the threat is a false threat, if what is going on is a combination of incompetence, politicians saving their skins and sacrificing the Muslim community - that's a really important story," said Holmwood.

This article is available in French on Middle East Eye French edition.

Middle East Eye delivers independent and unrivalled coverage and analysis of the Middle East, North Africa and beyond. To learn more about republishing this content and the associated fees, please fill out this form. More about MEE can be found here.